An Agreement between Binham Priory and people of Binham 1432

To be a medieval prior was no sinecure. On the domestic side, he was responsible for the well-being of his monks and retainers, for the assets and income of the priory. As a landowner he would hold manorial courts and administer justice and play an important role in the life of villagers who were dependent on him. On mature reflection, he might have seen this as the easiest part of his life.

The priory itself was a dependent cell of the mother-house, in the case of Binham this was the Abbey of St Albans in Hertfordshire. Abbots in general, liked to stress the word 'dependent' and frequently interfered in the running of the priory, holding visitations, checking accounts, and imposing their will when they thought it expedient. On occasions this lead to tensions between the abbot and the priory; from the abbot's point of view the priory and its monks were under obedience, but from their point of view they lived most of their day-to-day life in isolation and independence, and external interference was as unwelcome as it was disruptive. This mutual animosity could spill over into the national political arena, as it did in 1212 when Prior Thomas and Robert Fitzwalter ranged themselves against the abbot and King John, and again in 1319 when Prior de Somerton, Walkefare and Thomas of Lancaster aligned themselves with the Marcher lords against Abbot Hugh , the Despensers and Edward II.

Problems could also arise closer to home. In a number of priories in the country, the nave or part of it, was used as the parish church. This could lead to constant friction between the two, as the parish church came under the jurisdiction of the Bishop not of the abbot. The nave in Binham was divided from the Choir of the priory, by the low pulpitum wall, so that any services conducted in the one part could easily be heard in the other. Then there was the question of who rung bells and when, what processions should be undertaken and who should lead them and so on. Minor problems perhaps compared to armed warfare, but of vital importance to the parish and its clergy, who felt that they were over-dominated by the priory and its requirements.

The Experience of Wymondham Priory.

Wymondham priory was another Benedictine priory dependent on St Albans, lying some 30 miles south of Binham. Paul Cattermole writes:

The physical separation of the monastic choir from the parish church in about 1385, and the removal of the parish bells to the new tower, was the start of a long-running dispute between priory and parishioners; a further source of conflict arose in 1399 when Prior Walsingham set out to gain tighter control of the parish church. On a pretext of poverty he secured a licence from Pope Boniface IX that allowed him to appropriate income that since 1221 had supported the vicar. On the death or resignation of the present incumbent, his income (valued at thirty marks) would be added to the monastic income (valued at six hundred marks); and the parish church would be served by one of the monks or a secular priest appointed by the prior. The money cannot have been particularly important; but the right to appoint and dismiss the parish priest without reference to the bishop was worth a petition to Rome. When Bishop Wakeryng came to Wymondham in 1409 there was no ringing of bells to greet him. The monks claimed that as Benedictines they were exempt from the bishop's control, and probably felt that to ring the bells would be an admission of their dependence; while the parishioners could make the point that they had no bells of their own to ring without the prior's agreement. The bishop seems to have blamed the parishioners for the lack of respect, and as a result he placed the entire town under an interdict, which meant that all were denied the sacraments until reparation had been made.

This may have been the catalyst for the violence that caused Prior Boydon to seek protection; and twenty-four of the principal inhabitants of the town, including the four churchwardens, were bound over to keep the peace in July 1409. The large sums of money involved inflamed tempers, and the parishioners objected to the high-handed way in which the monks continued to collect their dues at the parish altar. Thomas Growte assaulted a chaplain in the church, tearing off his vestments and preventing him from saying Mass; and a succession of violent incidents followed, including a disturbance on St Bartholomew's Day when the prior's men were beaten with clubs and threatened with daggers.

During the autumn a group of parishioners set about asserting their rights in the church and churchyard, and the record of their actions suggests a considered campaign, rather than a hot-headed response to provocation by the prior. There was no wanton destruction of priory buildings, and the offences reported by the prior can be seen as a logical response to the parishioners' claims. In October 1409 they hung three bells in a makeshift framework above the north porch `to the disturbance of the holy offices of the said prior and convent, where there used not to be bells, and where no bells have hung within memory. The prior claimed that, although in the distant past a tower at the north-west corner of the church contained bells belonging to the parishioners, they had 'from time immemorial' been called to church by bells in the monks' south-west tower. The churchwardens ordered some ash trees in the churchyard to be cut down and sold, and turned the prior's bailiff out of the building where he collected the parishioners' rents. Two doors connecting the choir to the nave, through which the monks came to collect the parish offerings, were securely boarded up. Cool-headedness eventually gave way to violence early in 1410, when a mob entered the church and insulted the prior, who fled to the safety of his private chambers. The monks were too frightened to enter the church, and there was no sung Mass to celebrate the festival of the Epiphany. Peace was only restored when two officers sent by Sir Thomas Erpingham appeared on the scene.

Matters were now serious, and in February 1410 orders were given to take down the offending bells and to unblock the doorways connecting the priory to the parish church. As the matter was pursued through the courts, the parishioners stoutly maintained their innocence; and the Archbishop of Canterbury wrote to advise them not to attempt to assert their rights while the matter was before the court. In particular they were forbidden to reinstate the bells, either at the priory or elsewhere in the town. During the summer of 1410 an agreement was reached whereby the prior continued to enjoy certain rights in the parish church, and the parishioners were entitled to rebuild the north-west tower and hang their three bells in it. In the event the bells were transferred to the south-west tower, but the more impressive tones of the convent bells were a constant irritation to parish pride. Three thousand inhabitants sent a petition to the king in which they complained that they could not hear the bells in their own low tower, that they never knew when to come to church, that their children were dying unbaptised, and that others were dying without the benefits of confession and the sacraments. The logical site for the parishioners' tower at the west end of the nave belonged to the priory, and it was not until 1445 that the matter was resolved, probably as part of the deal which secured the elevation of the status of the priory to that of an abbey.1

The Experience of Binham.

In 1431 bishop William Alnwick2 of Norwich decided to conduct a visitation of the parish church of Binham.3 Relations between the bishops and the benedictines had been strained for some time, the latter claiming exemption from jurisdiction and therefore visitations by the bishop – about 1400 Archbishop Arundel of Canterbury paid a visit to Bury St Edmunds (another benedictine house) where he was sumptuous entertained as befitting his office; but no bells were rung, and he was escorted to the abbey, not through the main gate, but through the cemetery4. A similar question of jurisdiction was to boil up in 1433 between the abbot of Bury St Edmunds and bishop Alnwick, in which Henry VI had to intervene, the case then being passed to Archbishop Chichele who ultimately decided in favour of the abbot. As far as Binham was concerned, a lawsuit in the twelfth century had decided that the exempt status of the priory, did not apply to the parish church which remained under the jurisdiction of the bishop.

William Bryt had been appointed prior of Binham the year before, and now decided that a point should be made about the bishop's jurisdiction and his rights of visitation. The monks withdrew behind their own walls, refusing to ring their bells on his arrival and denying him entrance to the priory.

The parishioners for their part saw this as a golden opportunity to air their grievances against the priory, which had been boiling up for some considerable time. They told the bishop that the coldness of his reception was not due to them; they had hardly any rights in their own parish church as the monastery's exemption meant that everything belonged to 'the somewhat uncouth prior'. They had no freedom to use their parish church in a way that other people took for granted in their parishes; they had no bells of their own, or they would have rung a solemn peal on the bishop's arrival; they had to come to meet him in their 'rustic garb' as they were not allowed access to the vestments they would have worn to greet him in a solemn procession. They asked for the bishop's help. The bishop thanked them for their good wishes and gave them his blessing, before riding through the centre of the village to hold his visitation. As far as the priory was concerned, for the moment he held his peace.

It soon began to dawn on the monks that this time they had gone too far. By locking the priory gates they had denied the bishop access to the parish church, which was undoubtedly under his jurisdiction; they had also refused the local populace entry into their own church. It was time to sit down and talk before the situation escalated out of control.

The people of Binham realised fairly rapidly that, for once, they had the upper hand and the monks were in difficulty. They decided to broaden the talks from simply their use and rights in the nave of the priory, to include the whole way in which the monks were running the manor. They had to be treated as copyhold tenants rather than bondsmen. After protracted negotiations an agreement was signed between the prior and Convent of Binham and the tenants and inhabitants of the village on 14 September, 1432, the full text of which is given below.

Binham Manor and Village

Certain customary payments were made to the lord of the manor when land was bought, sold or transferred (known as fines). In Binham this had been a charge of 4s per acre. If however villagers wished to sell buildings (shops, messuages or cottages) without any adjoining land there was no fixed charge, which meant that the lord could charge whatever he willed. Under the new agreement these fines were regulated: the fine of 4s and acre was reduced to 2s, and buildings without adjoining land would be fined according to the value of the property. A house that would sell for 10 marks (£6 13s 6d) would make a fine of 6s 8d - then, on a pro rata basis, the greater or lesser the value of the house, the greater or lesser the fine.

Another bone of contention was the responsibility of the priory or the villagers to maintain and repair local roads. Today we would refer to the roads of the time as 'dirt tracks', so their repair would need hardly any financial investment, but would require a considerable amount of concerted labour. It was agreed that all parishioners and residents in Binham should be ready 'with the Prior of the same place for the time being to mend and repair or cause to be mended and repaired' the common streets and the king's highways in Binham, 'every man at his own proper Expense and Charge.' The day or days to do the work, agreed between the prior and the constable, together with other leading villagers, would be announced by the bailiff in the church, and any absenting themselves would have to pay at least 12d for each default. If the priory should suffer any loss through neglect inplan of 1655 repairing these roads, then the reduction of fines relating to land and property would be void.

Another bone of contention was the responsibility of the priory or the villagers to maintain and repair local roads. Today we would refer to the roads of the time as 'dirt tracks', so their repair would need hardly any financial investment, but would require a considerable amount of concerted labour. It was agreed that all parishioners and residents in Binham should be ready 'with the Prior of the same place for the time being to mend and repair or cause to be mended and repaired' the common streets and the king's highways in Binham, 'every man at his own proper Expense and Charge.' The day or days to do the work, agreed between the prior and the constable, together with other leading villagers, would be announced by the bailiff in the church, and any absenting themselves would have to pay at least 12d for each default. If the priory should suffer any loss through neglect inplan of 1655 repairing these roads, then the reduction of fines relating to land and property would be void.

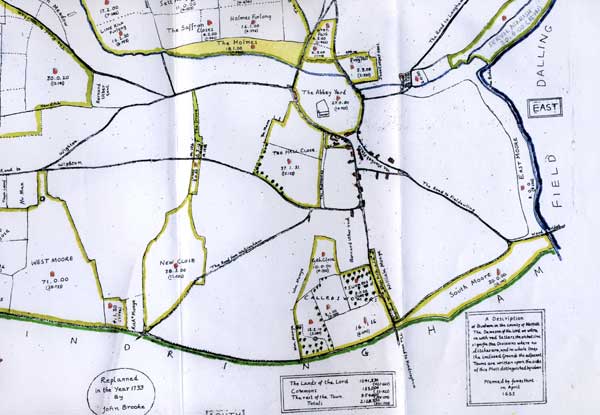

Also in dispute were the four 'more's, raising the question of grazing land. The priory regarded some as their property, but the agreement implies that the local residents disputed their title to the South More. A compromise was reached in which the residents undertook not to challenge the priory's right to the South or Middle mores but were given certain rights in regard to Middle More.(Probably the section in yellow, labelled The Holmes, on the 1655 map opposite - replanned 1732).They could feed and pasture their cattle there, providing they staked them so that they would not wander into the prior's grazing ground from the 25 August until Lady Day (25 March). They could also pasture their sheep and pigs there from the 29 September until 24 June, but the numbers were limited to 4 sheep for every acre a man owned. The priory for its part, undertook to keep their pigs off the commons from 25 March until 29 June, and generally keep off the common pasture called West More.

The Parish Church and Priory Nave

With the priory nave being used as the parish church, conflicts of interest soon became apparent. The villagers were aware that their church had been there before the priory was built. Since the church had been demolished to accommodate the nave of the priory, they did not consider their use of the nave as a 'grace and favour' from the monks; on the contrary, they had worshipped there before the priory was even thought of, and it was their right to continue to do so. The monks saw things differently. The priory had been founded by Valoignes, and they had been instructed to build it on the site of St Mary's church. At the heart of their vocations was the constant round of offices, and everything had to be subject to it; their life, the parish's life. They had built the nave, and the villages should be grateful for such a magnificent building in which to worship; the least they and their vicar could do, was fit in with their worship. The priory came first, the village (which they owned anyway) came second.

When the villagers looked round at the other parish churches in the area, they felt emasculated, suffocated by the heavy priory hand. Unlike others, they could not do what they wanted in their church; they could not beautify it, improve it, even worship there when they wanted. They had no bells to summon people to worship, no church tower to advertise their presence. They could not even have a procession through the village without the monks taking over.

The tower and its bells stood at the centre of the church above the crossing, but with the pulpitum separating it from the parish access to the bells was limited to the monks. The agreement allowed the parish to set up, at its own cost, a bell, of no more than 800 lbs weight, above the nave roof at the western gable, providing that no damage was done to the walls or window. The bell was to be used to summon the people to church, but not before 6 a.m. nor after 6 or 7 in the evening. If they wished to ring at any other time, the sacrist had been informed the evening before. Anyone ringing the bell outside the agreed hours would be fined at least 40d in the prior's court. (This would be something like the equivalent of ten days' wages for a working man.)

Processions had apparently been a bone of contention between the two parties, with monks and people forming up separately, each keeping to their own procession, and seemingly singing their own music. The new arrangements were carefully set out. In future, on the principal festivals of the year there would be a joint procession with everyone singing "with one voice and mind". The monks would come through into the parish church in procession to be joined by the vicar, parish choir and people. They would process together through the church and round the churchyard, only dividing when the monks entered their cloister, from which the parishioners were excluded.