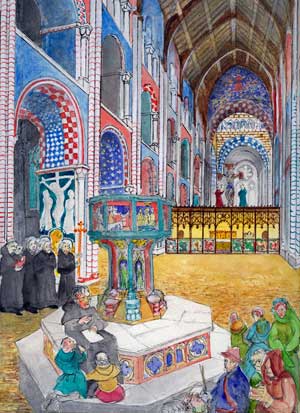

As we enter the church we are greeted by a buiding which can easily overwhelm the senses; our eye travels from the late medieval font, past the early English columns to the old Norman arches. It is easy to think that it has always been like this, but over the years the architecture has changed, the bright decoration inside has beenremoved at the Reformation, even the furniture has been renovated and moved around. This has happened to most of the medieval churches in this country, not simply because of political directives ( e.g. the Reformation, Commonwealth) but because social conditions and ways of thinking moved on, so that the insides of our churches have reflected the needs and feelings of those who worshipped there at different times in its history. It is a living church, supporting and supported by a dedicated congregation of people who through the centuries have ‘made it their own’.

The Church as it may have looked in late medieval days. The decoration is based on the surviving paintings at St Albans, the mother house. Watercolour by A. R. Hundleby

The predominant style of architecture is Norman, dating from the 1130s, more than one hundred years earlier than the west front. The seven bays of the nave had always been used as the parish church of Binham, but when the priory was dissolved during the Reformation of the 1530s, the pulpitum, which had divided the nave from the holy monastic part of the church, was extended upwards and a Tudor domestic window inserted, to seal off the church so that the rest of the monastic church could be dismantled.

This design is thought to be unique (notice head far left)

Billet moulding

zig-zag moulding

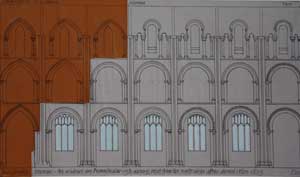

It seems likely that the nave remained unfinished for a long time before the west end was added. It is interesting to see the join between the two architectural styles at the west end of the nave. The change can be seen running diagonally upwards because more building work was complete at the ground level and as the builders progressed upwards and westwards, they built in the latest style, using pointed arches rather than round, and the stiff leaf capitals of the Early English gothic style.

The original foundation documents of the priory state that it should be built on the site which was occupied by the parish church of St Mary. The site of this church is unknown. It seems probable however that it was located towards the west end of the present church. The immediate building undertaken by the monks would have been the presbytery, chapter house and essential domestic structures, during which time St Mary's would have remained standing as the parish church of the village. This may in part account (other than a dearth of funds) for the strange fact that the west end was left incomplete for so long, for it would not have been too dificult to add a west wall at any stage in the construction process. It could even have happened - and this is pure conjecture, for which there is no direct evidence - that the parish felt they were being 'taken over' by the priory and resisted the demolition of their church. Throughout the middle ages when a priory nave, or part of it, was used as the parish church, there was frequently friction between the two parties over rights, the ringinging of bells and the conduct of services. The low pulpitum (see sanctuary) divided the monastic and parochial parts of the church, so that whatever went on in one part of the building could be distinctly heard in the other, and this conflict of interest could easily cause tensions to arise (see Monastic Agreement). There was no question of simply demolishing the church, as St Mary's was under the jurisdiction of the Bishop not that of the priory, and he would allow neither his rights nor those of the parish to be usurped.